Twelve Tweeters – A clock

A clock with roots that occasionally hoots.

The time it can tell without even a bell.

Ask it nicely and it will tell you precisely,

But if no one’s around it won’t make a sound.

A dozen on their perch won’t leave you in the lurch,

The assembled dawn chorus will sing something for us.

To make time a pleasure – a real treasure – not just something to measure.

Why did I make this?

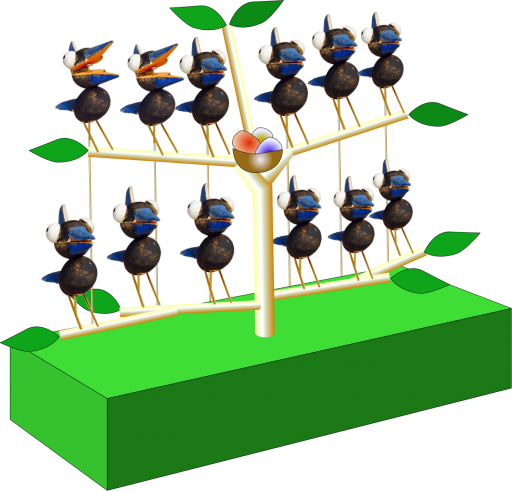

My aim was to make a clock that doesn’t look like a clock, and has no rotating hands to point to the hours and minutes. Cuckoo clocks came to mind and I really liked “bird’s tree” by the amazing Carlos Zapata, so birds seemed like a good start. Then I heard the BBC’s fantastic Tweet of the Day so I just had to make it.

Moving from the initial concept to the final design

Original design for Twelve Tweeters

Things that are interactive are more interesting, so if no one is paying attention to the clock it shouldn’t do anything. Only when you really want to know what the time is should it do anything. Things that constantly move eventually just become part of the background and you don’t notice them any more. Not to mention the wear and tear on the mechanism.

Remembering Swiss cuckoo clocks, I thought it would be fun if the birds sang to tell us the time. Of course I had to break the Swiss cuckoo’s monopoly and open up the tree to all sorts of birds, so I chose a different bird for each of the twelve hours of the day. To tell whether it’s two in the morning or two in the afternoon, you just have to turn around and look out of the window.

For the minutes, the birds had to do more than just sing and more than one servo motor per bird was too complicated so, after experimenting with a prototype, the idea of a two-stage movement popped up. Push a brass rod half way and the bird’s beak opens. Push the rod all of the way and its head lifts up away from its body, apparently stretching its neck.

So now, when you push the button to ask the time, the birds first stretch their necks to show the number of hours from 1 to 12. For example, if it’s 3 o’clock, 3 birds will stretch up. The second part then follows, where each bird is responsible for 5 minutes, so for example, if five birds open their beaks and the fifth bird sings that means twenty-five past the hour.

For the ornithologists, each bird has its own voice 1 – blackbird, 2 – bee-eater, 3- chaffinch, 4 – goldfinch, 5 – skylark, 6 – duck, 7 – greenfinch, 8 – great tit, 9 – mistle thrush, 10 – ortolan, 11- marsh warbler, 12 – nightingale.

For more drama, a light shines on the birds perched on their tree as soon as you push the button. This stays on for half a minute or so after a bird has sung the time and a “dawn chorus”, recorded by someone early in the morning in an English forest, then plays quietly in the background for a while.

In the end I also succumbed to tradition and allowed the cuckoo to briefly show off on every full hour. When we have visitors, this inevitably tickles their curiosity and is an invitation to push the button and see what happens.

A short video showing Twelve Tweeters in action

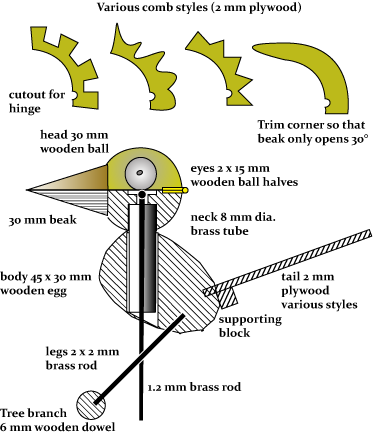

Materials for the birds

Everyone knows that birds hatch from eggs, so for each bird, I used one 45 x 30 mm egg for its body, one 30 mm ball for its head, two 15 mm ball halves for its eyes, 13 x 10 mm wooden strip to cut its beak, 8 mm brass tube for an extensible neck, a small free-moving hinge, 2 mm plywood for the comb, 2 mm brass rod for the bird’s legs and feet and 1.2 mm brass rod to connect to the servo arm.

Precisely drilling beech eggs and balls is tricky and although I made some jigs to hold them in a fixed position and drilled pilot holes, each of the 12 birds is slightly different, just like in nature. It wasn’t practical to screw or nail the hinges so I used fast-setting, two-component epoxy resin adhesive instead, taking care not to gum up the mechanism so that the beak still moves easily. The 1.2 mm brass rod is used to push the beak open until it reaches 45°(ish) and is restrained by the comb when the whole head will move up, exposing the brass neck which is fixed to the bird’s head but not to its body.

Making the birds move

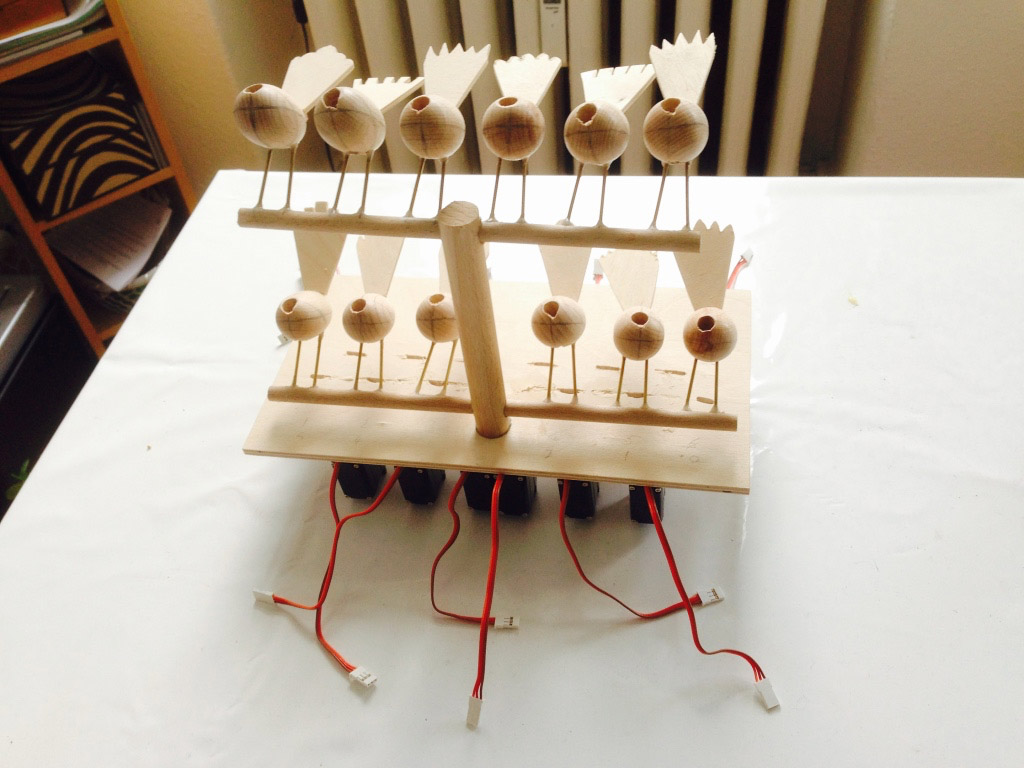

12 servo motors with wooden arms to push a brass rod up and bring the birds to life

Previous generations would have used clockwork I suppose, but the flexibility of being able to programme the movements and sounds electronically is ideal when you are feeling your way with no exact plan. That’s why the base hides 12 cheap and cheerful servo motors which turn through an angle set by an Arduino Uno computer. I collected the bird tweets wherever I could find them on the Internet and they are kept in a micro SD card, which is read by a Music Maker shield and this is what drives the loudspeaker. A real-time clock board then tells the Arduino what time it is. When I got fed up of having to reprogram the Arduino from my laptop for summer time and then for winter time, I added a new button on the back which sets the time to 12 o’clock when pressed.

Ready to paint

It’s hard to say how much time you spend on a project like this. It takes a while to settle on an idea and then try a quick prototype to see if it does what you intended. I suppose once you start to make 12 of everything, that’s when the “work” starts. Maybe I then needed a week to make the parts and assemble everything.

The brass rods moved by the servo motors to bring the birds to life

Twelve headless birds waiting for feathers

Something like this is never quite finished. Once I had painted it and put it all together I found that having a button on the side meant that the whole thing slides around when you push it. After I while, I moved the button to the top and that problem was fixed. Then I put it onto a shelf at the dark end of the room and each performance required the lights in the room to be turned up. I made a quick trip to get some LED strips, added a new socket to the back and a small power circuit and now everything is brightly lit as required.

Now I am content and every time I hear a cuckoo in the distance, I think, is it that time already?

Kim Booth – Bearded, bespectacled British bloke, born in the best bit of Birmingham, he blithely beavered to become a Bachelor in electronics, before boxing his bespoke belongings and boarding his bike to brave the borders, breaking out for beautiful Berlin. Belatedly, being both bilingual but bereft of business, he breezily became a broadband bandit, translating buckets of balderdash into Brummie British and by the by, builds bright beechwood birds.